Pt 1: Research

Gonna talk this week about designing mining equipment for the sci-fi game Astronomics – demo on steam right now! – And I thought I’d start with a little conversation about research and process (…that doesn’t really have on a much art in it but just stay with me) and maybe get to tap in a little bit into how someone like me who doesn’t do a lot of technical design learned a lot about how to get excited about that whole field through the research stage of this game.

So when I say research I really do mean fairly old-school research — and this is probably gonna be a theme with a lot of the posts about this game in particular, because I don’t think you can build sci-fi without some understanding of engineering systems and current scientific realities to then play with, you know?

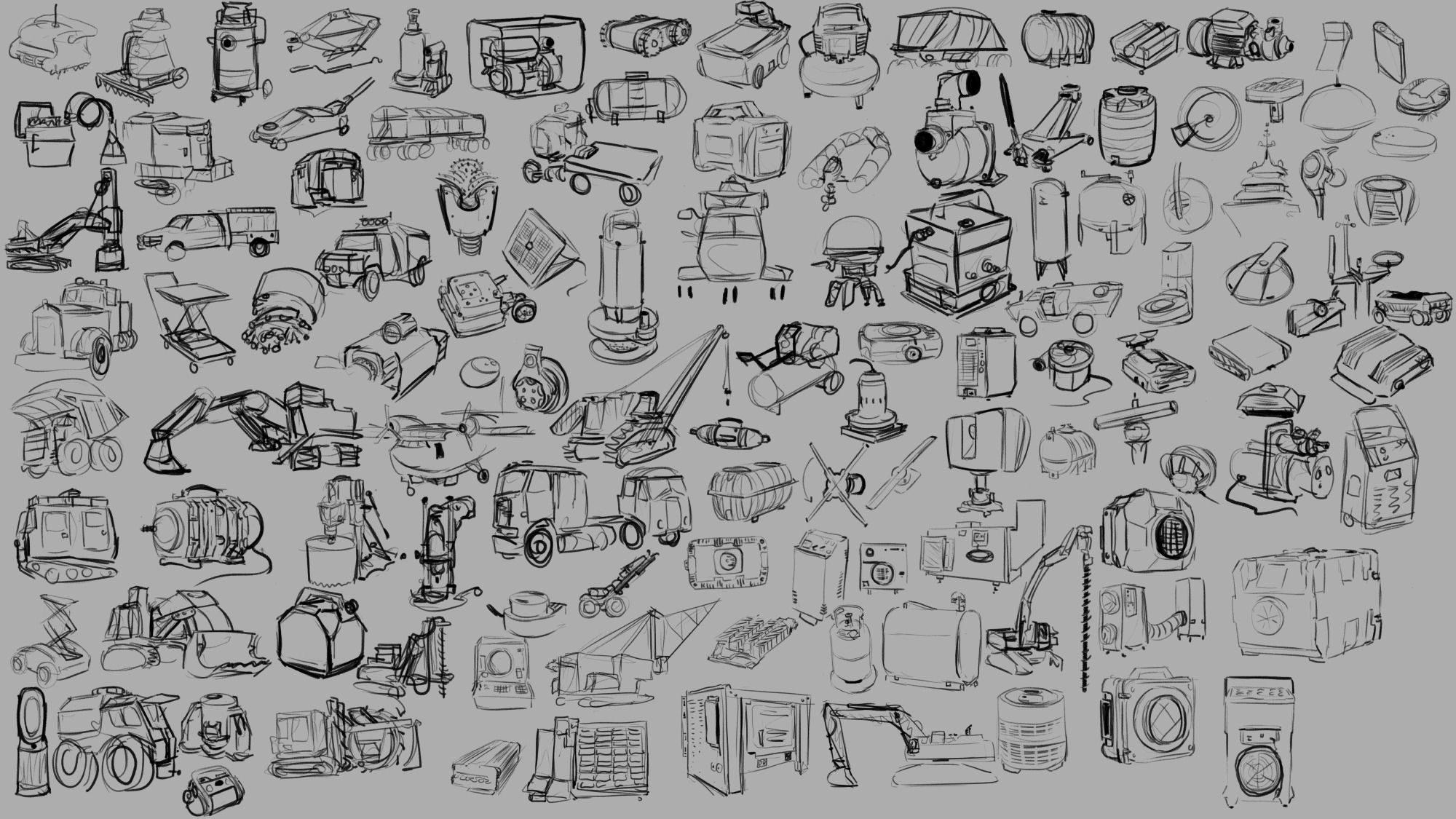

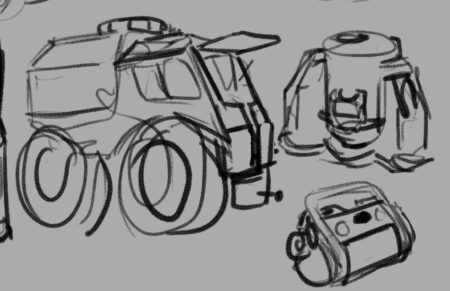

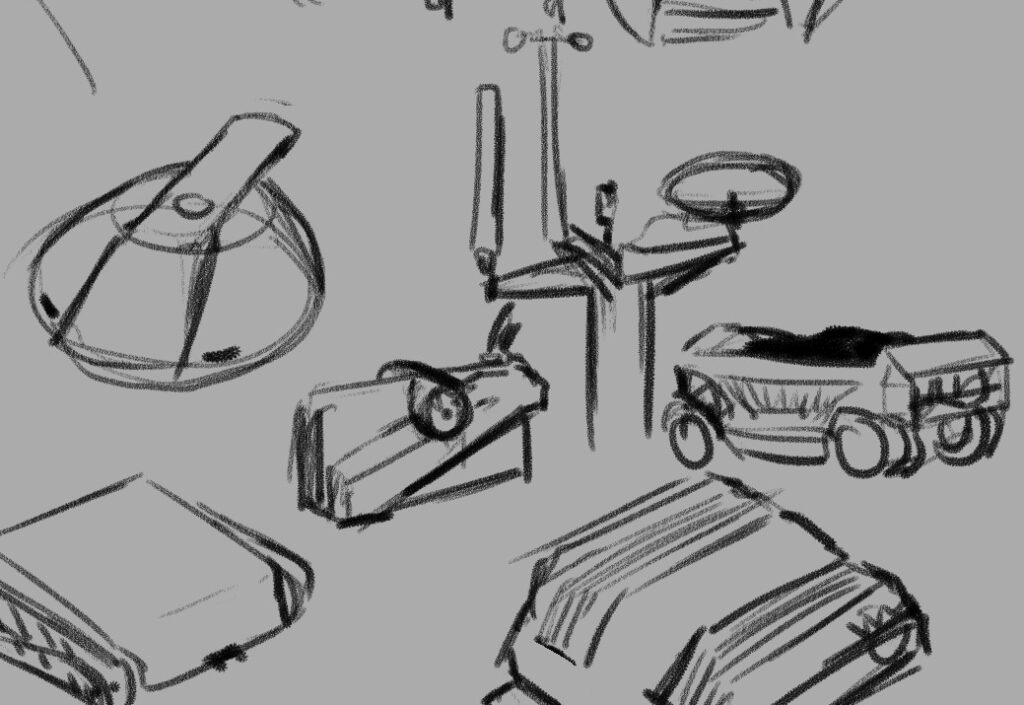

As you may gather from the trailer, Astronomics is a game about asteroid mining, among other things. Which meant that we had a lot of need for legit industrial feeling props and tools for the player to use, things that felt functional and believable without feeling complicated or delicate. I really enjoy the challenge of adding appeal to something that maybe people don’t always think about being appealing or fun or cute (this is never an absolute statement — there’s always somebody already able to see more appeal in any given subject and I could ever imagine) so part of the research stage is going and looking for that appeal. So above you can see a sheet of loose rough sketches I did in clip studio paint from reference that I gathered with the rest of the team and by myself that seemed relevant to some of the designs we were pursuing.

If you’ve had the chance to play the demo, you’ll know that it’s not just surface mining but we are going to be letting you mind gases and liquids and underground mineral veins as well — these are all things that people do in the real world of course, so process one was taking a quick look at those actual industries and then figuring out how I could condense that activity down into a pretty simple and easy to understand machine.

So turned out what we needed was something that drilled and dug, something that pumped liquids, something that sucked air, and all of these things needed to then produce some sort of container to hold what they had collected.

In a videogame you really need to communicate to the player why each act they do is significant and different from the others, and as the art director it was my job to figure how to do that through visual design of the tools they’re going to be using. So that meant that even though you could certainly store liquid and gas and solid resources in the same kind of box, I wanted to try and find ways to keep each thing feeling different. Best case scenario is that you’re able to look at a prop we’ve designed and know in a split second which of these three states of matter it will be containing; in the research stage one of the things I’m looking for is any existing visual language that we have (in this Western English-speaking North American videogame audience culture) that already solves this problem.

The great thing about industrial design is that they indeed have very intentionally tackled this problem. Part of it is purely physics optimization that the field of engineering has been working towards for human history. For example, when you’re storing liquid and you want to remove all of it from a container you probably don’t want something with corners — that’s how you end up with cylindrical liquid storage. When you’re storing a gas you’re likely keeping it under pressure, which means you need a shape that will withstand pressure evenly, which means you’re looking for something with literally no corners or edges ideally — and that’s how you end up with bubble-shaped gas storage like a propane canister. And then when you’re storing something solid and you want to use the space most efficiently and be able to stack whatever it is that you have packed it into, you have a box.

Real good news is, a box and a cylinder and a sphere are all wonderfully visually distinct shapes in a fantastically strong place to start when it comes to solving the question of storage. So then we get into the challenge of the machines themselves — what distinguishes a drill from a pump from a vacuum?

So that’s the beginning of some of the questions that you have to answer when you’re designing props for a game — in the research stage is only one of bunch of different ways you start figuring out these answers. But I want to talk for just a second a little bit about how I personally wrangle my research, because I am definitely not telling you this is the only way to do it. It seems like it may be worth explaining what I get out of this process and see if anything here make sense for you!

One of the reasons that I have this huge page of sketches, big and detailed or tiny and loose, all laid out in one place for me to look at, is because I personally learn and remember things more strongly by taking notes. With my hand holding a pencil ideally. And when they’re abstract concepts or verbal or numerical then I’ll use writing and I won’t have a problem with it, but my job at this stage was not to figure out abstract concepts or to find themes — my job was to solve visual problems. So my first order of business was visual research specifically. Now for me, that involves lots of things — I have a Pinterest board for any sort of subcategory of stuff I’m researching to just do enormous broad research with; then I probably bring most of those images into a huge working .PSD file and move them around to create groupings. And then I start drawing.

I really think that drawing is integral for me at this stage. I don’t think I could do this without drawing as part of my research. There’s so much that I just don’t bother noticing if I’m not going to be drawing the thing that I’m looking at; even the worst, fastest, sketchy as drawing makes me pay infinitely more attention to something then I do when I am simply collecting information mentally. I’m phrasing this in a somewhat exaggerated, self-deprecating way, but I really can’t exaggerate how much more I get out of things when I sit down and draw them. They talk about drawing is a way of seeing, and for me that’s a practice I’ve intentionally pushed and explored in my life.

The other thing, though, is that visual problem that I need to solve. Sometimes solutions to the problem aren’t obvious until they are visualized — it can be very easy to get distracted by things like surface details and miss the silhouette language, or vice versa, but when you are doing the drawing you have to wrestle with the silhouette and the details and make decisions about them. Visual trends appear way more clear when you are drawing something for the 10th time as opposed to simply seeing it for the 10th time. And all of the layers of cultural meaning and context that clutter up a photograph can be simply ignored as you transfer only what you need to a drawing, where you might discover something that everything else hid until then. Beyond that, one of the things you may notice about the sketches is that they are somewhat cartoony — I’m certainly trying to capture important details and be representational to a degree, but much like gesture drawing the human figure, researching this way lets me start finding out what the gestures are of these different sorts of subject matter. This is something that I knew about creature design, and about flora design, and one of the real joys of this game in particular was proving to myself that this gesture approach applied to industrial machines and technology as well.

I mean, I knew that there were cute trucks out there, but gosh.

I think if you are in need of something to reinvigorate a particular piece of subject matter for you — if you’re designing something that you are just not that excited about, or if you don’t feel challenged by the work in front of you — I really think sitting and sketching from reference can open up the complexities and help push you and your work farther. It certainly works for me and I know that the learning I did on this game is something I carry with me to future projects as well.

That seems like a pretty strong place to leave this post in particular, but I’ll be back later this week with more breakdowns and screen caps of the actual design process of all of our adorable mining equipment!

I would really love to hear from folks if you also engage in similar research processes before going into full design mode — or if you have a completely different way to get your mind revved up and ready to go, I would really enjoy reading about it!

In the meantime, if you’re curious about mining asteroids but it’s cute please feel free to check out the Astronomics demo on steam, I made an awful lot of visdev art for this and handed it off to some incredible game creators who have done some really impressive stuff taking their ideas and my ideas and running to honestly some pretty new and exciting places with them.

Leave a Reply