swap to chronological order of most recently posted

-

For the Aga Khan’s Dungeons and Dragons camp they wanted to go above and beyond a basic DnD game and take the kids into a very specific world – the world of the Shahnameh.

The Shahnameh is the longest epic poem (by a single author) known, written by the poet Ferdowsi about 1000 years ago. It tells the story of the mythic, legendary and historical past of the Persian Empire, from the creation of the world forward to the arrival of Islam in Persia in the 7th century, and introduces us to kings, demons, triumphant and tragic heroes throughout time. There is more than enough in the Shahnameh to create an incredible world for kids to game in, but what we were lacking, unfortunately, was time.

Because this was a pilot program, we had to focus in and be efficient in creating a world for a week’s worth of play, without spending time on things we weren’t going to get to. In the end, I had about two full days to prep things, so I really had to prioritize, and thankfully the museum staff had some great suggestions.

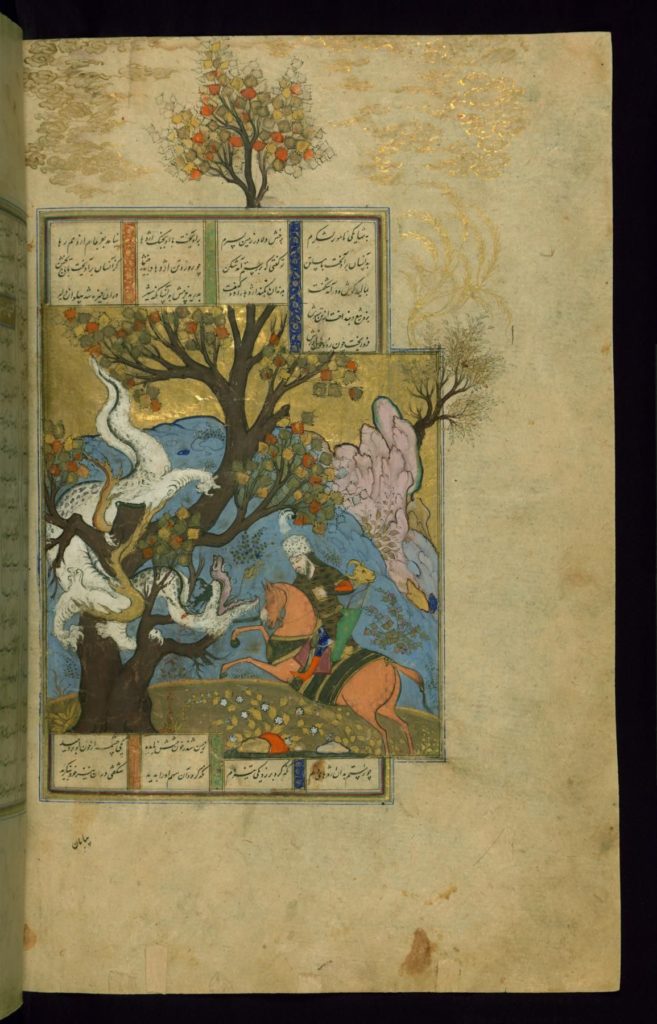

(image “Rustam Kills a Dragon” – from the folio created by scribe Muhammad Mirak ibn Mir Muhammad al-Husayni al-Ustadi, courtesy of WikiMedia) Firstly, they chose a specific story for us to hinge the campaign around – Rostam’s Seven Trials (also known as Labours). Secondly, they were able to provide me with a kids’ adaptation of a few of the key stories of the Shahnameh, including the Trials, which gave me not only a quick introduction to the poem, but also helped me get a sense of how to adjust things for the kids. I also had access to museum staff who had studied and read all of the Shahnameh, which was incredibly helpful and, I think, important, because if you haven’t put it together yet, I was a white woman running a program at a museum about the history of Islam for a majority POC group of kids, set in the world of a poem that has survived a millennium as a cornerstone of Persian history, culture and nationality. It felt really important to use as much of the time I had as I could to talk to experts, and I’m really grateful they were available to me – I only wish I had been able to make better use of the resources they were able to get to me.

So, given the time I had, here is what I focused on to bring the setting to life for the kids.

Firstly, I provided a huge list of Parsi names, so that players and GMs could choose names that belonged in the world of the Shahnameh. Because some of our players were Persian, there was some overlap between fictional names and player names, but this didn’t seem to push them out of the game at all – they seemed excited by it. I was less worried about the players and more worried about the GMs, though – all of us with a grounding in Tolkeinian fantasy have a persistent background radiation of fantasy name parameters that can either ignore Middle Eastern or Asian names or use them in explicitly orientalist ways. Having a list of names we stuck to helped us avoid slipping that error into our games.

The next thing that seemed important was to set the stage of the setting with some visuals. There’s a wonderful scholarship that has connected much of the setting of the Shahnameh with real world cities, and I was able to find images of the six main environments we were dealing with to help bring the kids into the world. Not every setting had a clear real world parallel, so some guessing had to be done, but I tried to keep things local to the areas we did know. Visuals worked AMAZINGLY, visuals are the best, I am going to spend a LOT more time on visuals in future campaigns. I wish I’d had a lot more visuals of architecture, clothing, armour, weapons, animals, people, monsters and so forth, to be able to bring things to life at the table.

The next thing I did was go through all the player-facing information – their character sheets, the lists of moves and so forth – and wipe out anything too Tolkeinian and replace it with Persian counterparts. This was a surprisingly nuanced and complex process I wish I had spent more time on – whether it was the deities the Acolyte dealt with or the magical swords the Fighter used, I had to make sure I at MINIMUM renamed them so they weren’t all “Eowynia’s Blade” and “Thorsson God of Lightning” and so forth. Thanks to Daniel Kwan’s suggestion, we also filtered the classes so that the only magic available was healing and light magic, no wizardry, because in the Shahnameh magic is the domain of demons, and chaos, and we wanted to keep magic scary, surprising and (probably) evil in the eyes of our players. This gave the world a very sword and sorcery feel, honestly, which is definitely in my wheelhouse, and seemed to work fine with the kids as well. Being their first RPG experience was a privilege that way – no one knew enough about wizards to be upset they couldn’t play one.

I also plotted out four campaigns, but I’ll get into that in my next post.

The biggest challenges of building a setting from the Shahnameh, besides just the sheer size of it, was that it focuses on kings and heroes, gods and demons, and is missing a lot of the granular, day to day, on the ground kind of information that brings a game setting to life for the players. If I’d had more time I would have liked to do a lot more research into not only the Shahnameh, but also into a few different eras of Persian history from an archaeological and anthropological standpoint, so I could have a palette of currency, clothing, cultural mores, social roles, songs, jokes and more for the GMs to work with. As it was, we did our best, but I worry about how much that eurocentric Tolkeinian fantasy background radiation crept through, and would like to spend more time tightening up our setting in future.

All in all, though, it was an exciting challenge, I learned a lot and the kids seemed to get into it in a big way, especially since their campaigns were following in the footsteps of Rostam. But I’ll tell you all about those campaigns, and Rostam’s Seven Trials, next post!

-

For our Dungeon World in the Shahnameh summer camp at the Aga Khan Museum, one of the challenges in the prep was writing adventures for up to four groups of players that kept them all wrapped up in Rostam’s Seven Trials, without tripping over Rostam or changing his story, and didn’t have them competing with each other or deciding some groups or GMs were doing things “wrong”.

I initially considered writing a single adventure and sending each group down the path on their own, as if each was playing their own playthrough of a videogame, but that’s ignoring some of the best things about tabletop games – collaboration and spontaneity. In the end, after a great brainstorming session with Daniel Kwan (who runs a huge collaborative multi-group epic campaign for kids at the Royal Ontario Museum) I came upon a shared map solution.

The way it worked was, I broke down the route that Rostam travels in the Shahnameh as he pursues his Seven Trials. He travels from Zabolistan, through several distinct regions, to Mazanderan, and fights a climactic fight in a cave in the mountains. For our campers, I decided that they too would travel this route, but always a step or two behind Rostam, so they could collect signs of his passing but not interfere with his story – instead, his story would interfere with their quests. And I ended up writing four adventure seeds for our camp, so that each group was on their own quest that didn’t have them racing or fighting each other for “win” conditions.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, it was a beautiful dream to think that groups of gamers would commit to a linear adventure path, especially kids, but having a strong motivation for them to get moving turned out to be enough to get them started, while the lure of the map they were all using kept most groups moving. I would draw the map on the whiteboard every morning and we would often go over our progress by citing things we’d found in each region, which kept kids focused on their travels and also allowed them to share narratives from their game with each other and for us all to discuss them. The other thing we did, which is pictured above, is take over a big bulletin board in the hallway outside our classrooms, divide it into the regions and let the kids make landmarks, monsters, PCs (player characters, NPCs (non-player characters) and other notable memories out of craft supplies and we stapled them to the board. This meant that even when players weren’t invested in the details of their own quest, they were still curious about and slightly competitive with the other groups when it came to making it to Mazanderan. This wasn’t a complete fix, but I think it did help the GMs keep their groups in known territory, even when the storylines were well off the rails.

These were my first adventures and I learned a lot from my own group as well as the other three GMs and their groups. The format I used was incredibly bare-bones – each adventure was given a plot hook, an NPC, a creature and a cool piece of treasure I statted out. Beyond that, they all shared the same regional breakdown, where each region along Rostam’s path was described and potential encounters and discoveries were listed, as well as a few signs of Rostam’s passing that the GMs could sprinkle in to remind the players of their connection to the story. I got this idea from Jason Lutes’ “Perilous Almanacs”, a Dungeon World-friendly collection of regions described via their contents, all nicely laid out for GMs to grab what they liked from. To keep continuity, the GMs and I would have a short meeting at the end of every day. If anyone’s players burned down, say, a castle, we’d all hear about it and only castle remains would be found by any followup adventurers. I think, in future, more hook-specific writing, more fleshed out statistics for a wider range of encounters and way more possible side quests and such would really flesh out potential adventures for group like these, where everyone was new to the idea of gaming but also easily distracted.

Now I wrote these adventures for the museum, so I can’t share all the details with you, but next week I’m going to talk a bit about how we used the museum’s exhibits, artifacts and the story alongside arts and crafts to flesh out the educational aspect of the camp and also help immerse the kids even further in the game. That will probably be my last post on this subject, and we’ll return to your regularly scheduled research posts – thanks to everyone on my Patreon for making these possible!

-

Gaming at the Museum – Combining Gaming with Crafts, Museum Collections and Storytelling

posted:

updated:

So in addition to running tabletop games twice a day for the kids’ summer camp I ran at the Aga Khan Museum, we supplemented gameplay with a few different things: firstly, we spent time every day in the museum’s collection and travelling exhibits; we read aloud stories from the Shahnameh; and we did hands on creative exercises that fed into both learning about the museum collection and enhancing the gaming experience.

Our first craft, and the one that paid off the most over the entire program, was making handmade journals. I was definitely inspired by the way Sword and Backpack uses a journal for each player as well as the GM; and as a selfpublisher, I know that making a Real Book is an incredibly empowering exercise for folks of any age. We used basic craft supplies for the covers and ¼” grid paper for the interiors, and the counselors saddle-stapled them. Each camper got to decorate the covers, “age” the interior pages and add bookmark ribbons or felt latches to theirs to make it special and ready for adventure. Each GM also made a journal, initially because we were doing demos for the kids and making journals is fun, but it turned out that they were incredibly useful for everyone in the camp, not just the campers themselves! GMs kept campaign notes, monster stats, secret plot developments and more in their journals, and I can’t imagine running a game without one now.

Once the kids all had a journal of their own, they had a place beyond their character sheets’ limited space to keep all sorts of information about their gaming. For some campers, this meant that they recorded everything that happened in the game in their journal – for others, they kept track of important clues, or of all the treasure and neat items their character acquired. Some kids immediately copied the shared map I laid out on the board on the first day into their journals, and tracked their own progress through it and referred back to it in game quite a bit. Others drew their characters, or monsters or NPCs they encountered, in the pages of their journals. The best thing was that each kid had a personal and private space to process their adventures and personalize their story.

The journals were useful beyond the gaming table as well. As I mentioned, we spent time each day in the permanent collection and in the travelling exhibits at the Aga Khan Museum, and having journals and pencils in hand helped the campers go from simply passively listening or looking as we introduced them to the material, to taking notes, organizing information and concretizing concepts into writing or drawings that they could take with them back into the classrooms or home.

The museum’s permanent collection was a little at odds with our focus on the Shahnameh, as it is focused on the history of Islam, which is the era AFTER the Shahnameh. However, the Aga Khan Museum has an incredible collection of illuminated manuscripts of the Shahnameh from across a broad swath of history, which gave us so many incredible talking points. The collection includes tablets with the images on them, which allowed the kids to zoom right in on tiny details. The paintings were amazing information resources and I was excited to share them with the campers, but in future I will spend more time teaching the kids how to parse those complex illustrations before setting them loose. Nevertheless the kids were able to use the tablets and the mounted manuscript pages to learn a lot about animals, monsters, and the kinds of clothing and architecture that would be part of their characters’ worlds in game through the illuminations. We also made use of the sculptures, decorative artworks and the textiles to help the kids glean information about what values and priorities were like in the world of the Shahnameh and afterwards.

The journals were a great anchor piece for the campers as they explored the collections – there was always a little knot of kids on benches or on the floor taking notes and drawing in them. The other amazing anchor was the game itself – campers were motivated to investigate the artifacts from their own point of view, with the intent of bringing this information into their gaming. Thus their own in-game needs and questions helped motivate them to look deeper and take good notes when they had access to the collections. I believe that using Dungeon World was extra helpful here as by the third day most campers had a clear grasp on just how much they could contribute to the world of the game, and could see the direct link between finding something interesting in the galleries and getting to encounter it in game.

Our other crafts over the week consisted of mini dioramas of the environments we were exploring, felt treasure bags and construction paper versions of treasure and equipment from in game, landmarks and monsters for the collaborative cork board map (including a few amazing 3D papercraft buildings and some narrative illustrations of battles!) and on the final day, character portraits, many of which were clearly inspired by the clothing, armour and weapons we had been studying in the illuminated manuscripts all week. As I mentioned in an earlier post, the shared map stood out to me as another incredibly powerful exercise that had the entire summer camp collaborating on populating an initially blank map in the hall and sharing stories with each other as they drew and cut out and assembled their landmarks and illustrations for it.

The final peripheral activity was the oral storytelling from the Shahnameh every day. I’ve worked with teens and adults mostly in the past and was awed by how much fun reading aloud to kids can be. Hearing their reactions to story moments and their guesses as to what comes next was definitely a highlight for me, but the best part was our discussions after each reading, where we talked about what had happened and what they thought of it all. We had some incredibly smart and investigative conversations about heroism in Rostam’s story – The kids had been paying close attention to his behaviour throughout his seven trials and when we talked about heroics they were quick to call him out on his attitude and how he treated people as well as his great deeds. We were able to dig deep into what it means to be a hero and a good person, and we were able to take those ideas of heroism into the museum galleries where other stories were shared via the illuminated manuscripts. Talking about what makes a hero was something that the kids were able to bring into their game, and I hope we introduced that classic D&D player tension of “Win All the Stuff vs Be A Real Hero” to a whole new generation.

Oh, I have one more note about the handmade journals before i wrap this up, and if this doesn’t encourage you to make them with your next group I don’t know what will: on the final day, as we wrapped up our crafts and finished our games and high fived all over the place, the kids decided that they needed to sign each others’ journals, as if they were highschool yearbooks. Each GM now has a journal full of notes from their game AND notes and signatures from all their gamers, and each camper has a journal full of notes from their gaming group and their fellow campers, and even, if they asked for one, from their GMs. It was a great way to wrap up the week and a wonderful artifact of my own that I will treasure.

So, this wraps up the Gaming at the Museum posts! Thank you so much to my Patrons whose support made this in-depth recap and analysis possible, and thanks to everyone who helped make the program itself possible, especially Alix, Casey and Jason, the best co-GMs a person could ask for. If you’re interested in reading more about museum gaming, keep an eye on Daniel Kwan’s twitter feed, and if you tackle a program like this yourself sometime please let me know all about it!

Finally, if there’s anything I haven’t covered, please feel free to drop questions in the comments here or tweet them to me on twitter, I’m definitely excited to keep talking about this!

Thanks all!

-

-

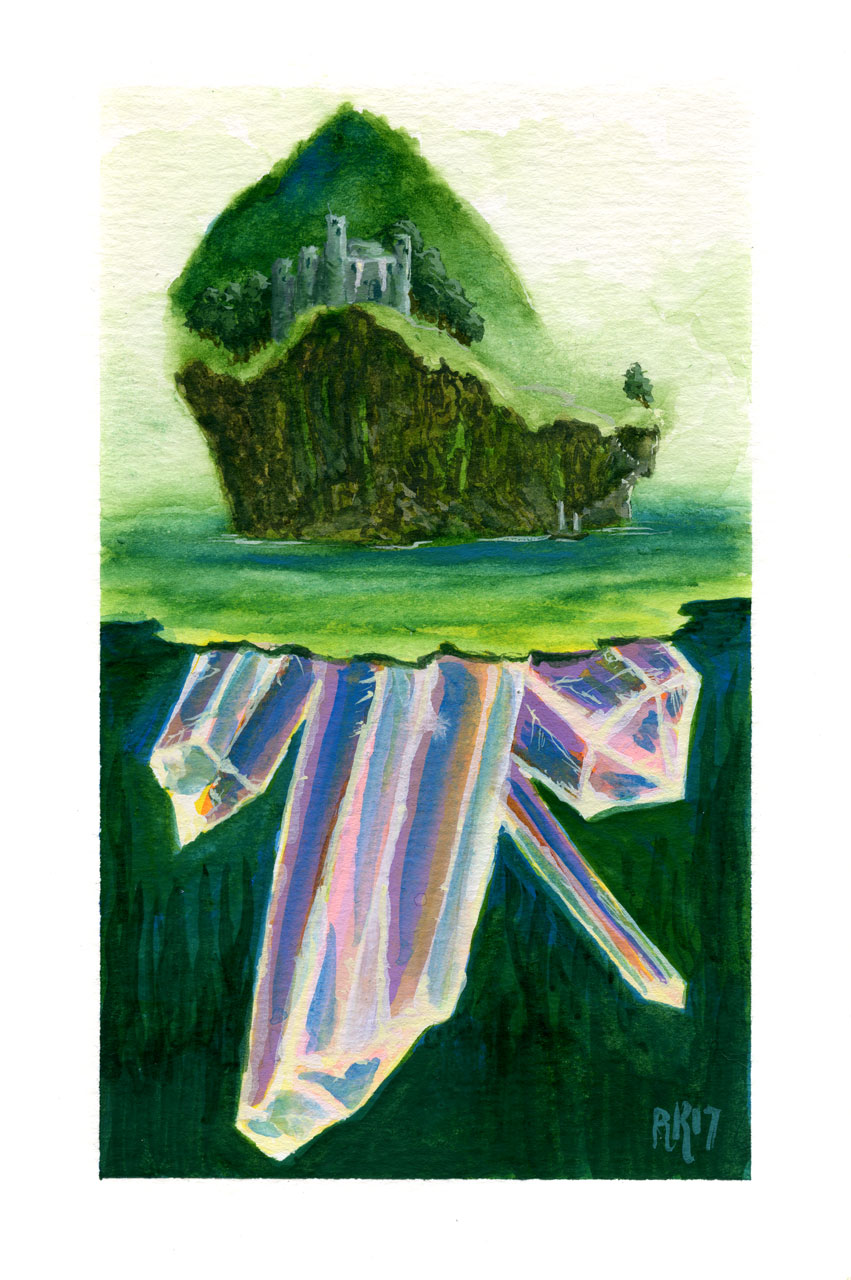

Crystal Island

posted:

updated:

tagged: building block, crystals, french river, geology, gouache, granite, image, space, storm clouds

-

-

-

-

-

Leave a Reply